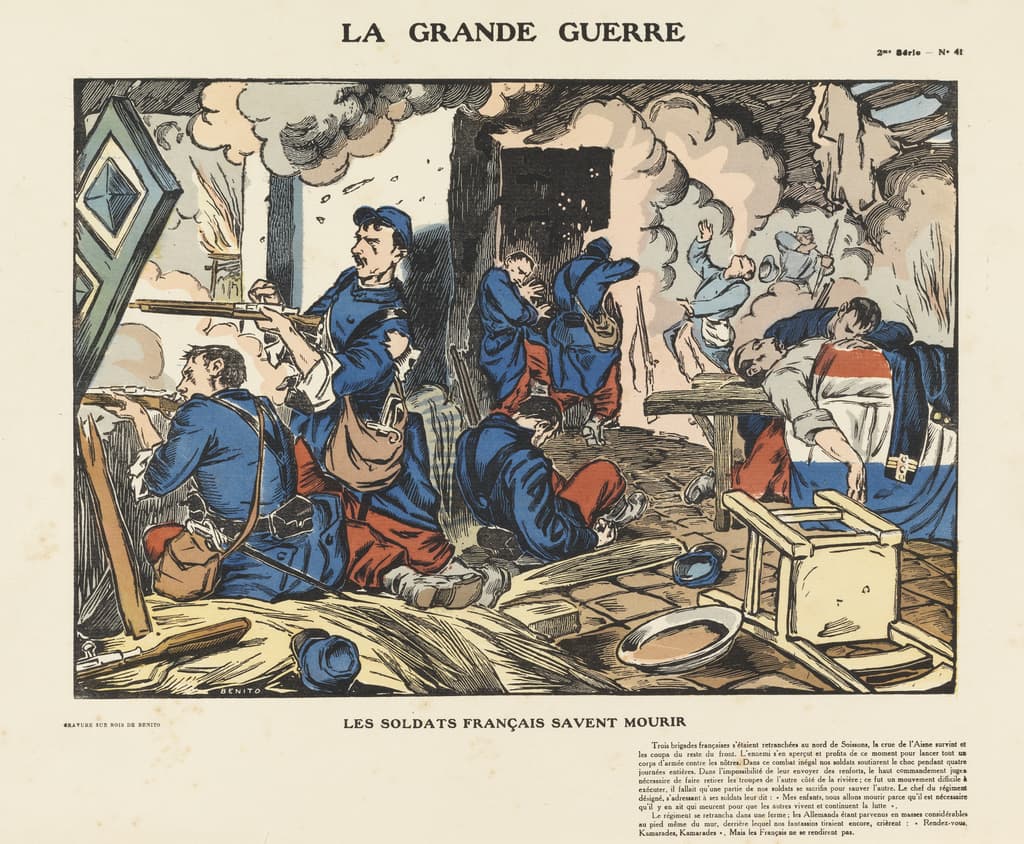

Eduardo Garcia Benito (1891-1981)

Les Français savent mourir

The French know how to die

Woodcut with hand colouring through stencils. Publisher: Tolmer & Co. 1915.

Given by Sophie Gurney 1994

No. 41 from the 2nd series La Grande Guerre .

No country had experienced so devastating a war in terms of casualties. An estimated 300,000 French soldiers died in the months of 1914 alone, a toll of around 2,000 deaths per day. At the start of the war prefects were instructed to keep the wounded away from the civilian population in railway stations and other public places. Notifications of deaths began to arrive in September. The French government, concerned about the public learning about the high numbers, banned the press from publishing the names of the dead. Emphasis was instead to be placed on their noble memory, another example of the attempt made by authorities to mould public opinion. Families who could afford it made their way east in order to recover bodies, since they had been unable to perform last rites for their dying during their final moments. But it was typical for families to receive very imprecise information about where and how a loved one died. Many men could not be identified, and their bodies were buried in military cemeteries close to the front line. In 1920 the French government passed a new law that allowed families to claim bodies for reburial, but, again, it was only an option for those who had the funds.

The French caption with English translation:

Les Français savent mourir

Trois brigades française s’étaient retranchées au nord de Soissons, la crue de l’Aisne survint et les coupa du reste du front. L’ennemi s’en aperçut et profita de ce moment pour lancer tout un corps d’armée contre les nôtres. Dans ce combat inégal nos soldats soutinrent le choc pendant quatre journées entières. Dans l’impossibilité de leur envoyer des renforts, le haut commandement jugea nécessaire de faire retirer les troupes de l’autre côté de la rivière; ce fut un mouvement difficile à exécuter, il fallait qu’une partie de nos soldats se sacrifia pour sauver l’autre. Le chef du régiment désigné, s’adressant à ses soldats leur dit : “Mes enfants, nous allons mourir parce qu’il est necessaire qu’il y eu ait qui meurent pour que les autres vivent et continuent la lutte”. Le régiment se retrancha dans une ferme: les Allemandes étant parvenus en masse considérables au pied même du mur, derrière lequel nos fantassins tiraient encore, crièront: “Rendez-vous, Kamarades, Kamarades”. Mais les Français ne se rendirent pas.

The French know how to die

Three French brigades were entrenched north of Soissons when flood water from the Aisne cut them off from the rest of the Front. The enemy noticed this and took advantage of the moment to launch a whole army corps against our men. In this unequal fight our soldiers sustained the clash for four whole days. Unable to send reinforcements, the high command felt it necessary to pull back troops from the other side of the river. It was a difficult movement to execute, but it was necessary for some of our soldiers to sacrifice themselves to save others. The head of the named regiment, addressed his soldiers thus, ‘My children, we will die because it is necessary that some die in order than others live and continue the fight’.

The regiment retreated to a farm. The Germans having arrived in a large mass at the foot of the wall behind which our infantry were still firing, shouting ‘Rendez-vous, comrades, comrades’, but the French do not surrender.